Beyond Disputes: Exploring the Three Dimensions of Conflict

Conflict and disputes are an everyday occurrence in all aspects of human society. They can be brief and trivial, such as someone trying to cut into a line at the grocery store; complex, personal, and emotional such as the separation of a married couple with several children; or large-scale, long-lasting, and ongoing such as the Israeli Palestinian conflict. Individuals in a dispute or conflict can be highly emotional, worried, or fearful, and they may launch into protests or claims.[1] Communication can be chaotic and unclear. The interchangeable terminology used to describe these occurrences calls for clarification and the need to define common elements and distinctions in these events.

This article will explore the evolving distinctions between disputes and conflicts, as well as recognize the shift or escalation of disputes and the implications for conflict practitioners (mediators) and parties managing disputes. To be an effective mediator, one must listen thoughtfully, recognize how individuals explain their disagreements, understand how disputes escalate, and identify critical factors to help with de-escalation and resolution. Understanding a dispute's creation allows practitioners to apply appropriate communication techniques, engagement methods, and mediation tools to help the parties reach a settlement or resolution.

Definition Background (History)

In reviewing the literature for a distinction between 'conflicts' and 'disputes', Carrie Menkel-Meadow (2003), a scholar focused on defining the field and practice of conflict resolution, proposed the challenge of defining a general theory of conflict management that would be universally applicable regardless of context or domain.[2] In 2003, Shonholtz responded with the following:

The General Theory on Disputes and Conflicts assigns disputes to transitional and mature democracies and conflicts to authoritarian regimes. The First Premise of the General Theory is that there are no conflicts in democratic society, only disputes, as democracy transforms conflicts into dispute settlement mechanisms. The Second Premise is that in authoritarian regimes there are only conflicts and politicized systems of settlement, not disputes. The Third Premise is that in international relations, national states can transform conflicts into disputes. In this article, conflicts are defined as those issues that lack a legitimate, reliable, transparent, non-arbitrary forum for the peaceful settlement of differences. Disputes, conversely, are pre-described as having recognized forums for their expression and resolution that meet the above criteria. In short, conflicts lack a viable "container" for the routine management of differences.[3]

This view begins to structure two aspects of conflict and disputes: 1. Whether the conflict takes place in a democratic or an autocratic society, and 2. Whether there are legitimate and transparent forums for conversations to occur.[4]

John Burton (1996) defines the differences in terms of the time frame and the issues in contention. He describes a dispute as a short-term disagreement that is more easily resolved with negotiable interests and needs. Whereas "conflicts are struggles between opposing forces, struggles with institutions, that involve inherent human needs in respect of which there can be limited or no compliance, there being no unlimited malleability to make this possible.",[5] suggesting that conflicts are inherently unresolvable. These definitions begin to define the differences between disputes and conflicts.

Naming, Blaming, and Claiming

Let's examine the initial starting point that we recognize that we are in disagreement. In describing the point of ignition and evolution of a dispute, Felstiner, Abel, and Sarat (1981) research posits a framework of Naming, Blaming, and Claiming.[6] This model describes a turning point when an individual transitions their internal narrative to verbally labelling the problem and associating it with a party or parties. In their words, a dispute starts as an "unperceived injurious experience" (unPIE) and then transforms into a "perceived injurious experience" (PIE).[7] According to Felstiner et al. (1981), once an individual feels that they have a "perceived injury", the following three elements must occur for it to become a dispute:

1. Naming: This is the most critical transformation point where an unPIE becomes a PIE. The individual's verbal or written communication will more than likely have the following characteristics: "they are subjective, unstable, reactive, complicated, and incomplete."[8]

2. Blaming: The PIE becomes a formal dispute or grievance by identifying shortcomings or flaws of the other individual(s) or organization.

3. Claiming: Communication occurs when the person voices their grievances directly with the other person or entity and asks for some type of remedy. If the remedy is rejected (verbal or non-verbal), a dispute then arises.

The action of naming, blaming, and claiming by the aggrieved party typically happens in a quick, emotionally fuelled outburst (verbally and physically) and is recognizable by all parties.

Three Levels of Disagreement

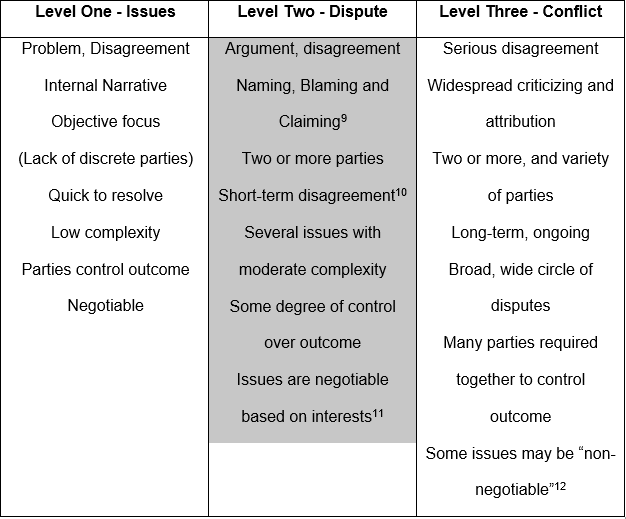

The literature review demonstrates a lack of a clear, mutually understood definition(s) of the terms "dispute" and "conflict". Inspired by the research, the table below may assist a mediator in distinguishing these terms more readily. The table, Three Levels of Disagreement, identifies key elements an individual may apply when describing or discussing their dispute(s). Level 1 relates to minor problems and issues where discrete parties may not exist. Level 2 is where most disputes occur and involves an active disagreement between identifiable parties. Level 3 disagreements are broader, systemic, and may involve long-term or historical conflicts.

Pinkley (1992) identified questions to help diagnose disputes and conflicts, such as: "Would you say this conflict involves one central issue or a number of issues? On a scale of 1 to 7, how intense or serious is this conflict? How long has this dispute been going on/when did it start? What do you really want to come out of this conflict? How would you like to see this conflict settled?"[13]

Building on Pinkley's work and utilizing the elements contained in the table, a mediator could create a customized tool to assess conflict situations. By developing related questions for each element in the levels of disagreement, the mediator can gather information to understand the scope and impact of the aggrieved parties.

Application and Implications

Managing issues at the lowest level of conflict can stop the progression towards a more significant, emotionally painful, and complex dispute or conflict. Mediators must help individuals organize their thoughts, comments, and claims as early and effectively as possible to minimize damages.

To illustrate the complex and intertwined relationship between disputes and conflicts, let's consider a recent example to demonstrate how various levels of disagreement can exist and progress on all levels simultaneously. On September 30th, 2021, Canada reflected on its first National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, created to explore the rich and diverse cultures, voices, experiences and stories of the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples.[14] As Canada struggles with acknowledging Indigenous challenges, how can we diagnose disputes and conflicts at each level of disagreement?

Microaggressions are a current example of a level-one disagreement. Initially identified by Pierce (1970) microaggressions are described as "everyday microaggressive acts, behaviours that consist of brief and commonplace verbal, behavioural, or environmental indignities that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative slights and insults (Sue et al., 2007). Central to the concept of microaggressions is the fact that they can be unintentional and often exist outside of the conscious awareness of the initiator."[15] Using our previous example, consider a situation where co-workers comment on the newly identified Truth and Reconciliation Day: "Great, a new vacation day – I love long weekends." or "Just a day for Trudeau to buy votes". One co-worker, Joe, who typically passes as white and has not publicly disclosed his indigenous heritage, overhears these comments. These thoughtless and derogatory remarks could have a negative impact on Joe and others. To address this issue, the mediator must reflect on whether the parties have sufficient self-awareness to realize how their words and actions are being perceived. Are his colleagues inadvertently retraumatizing the Indigenous party? Do his colleagues understand that their words are an issue? Although the disagreement is still invisible, it is present and able to ignite to the next level.

At level two, an Indigenous party gets passed over for promotion due to racial bias. For example, two candidates with the same technical qualification apply for the same job. The self-identified indigenous candidate has similar years of experience and can perform the job. For the mediator to diagnose this dispute, they must consider the following issues: awareness of employment and labour policies (from federal laws down to organizational policies), job expectations, years of experience, and skill requirements.

Level three recognizes that various jurisdictions in Canada continue to struggle with the negative impacts of colonization and ongoing massive systemic challenges towards Indigenous peoples in our society. Level three conflict is especially subject to external forces that are beyond our control, such as a recession or the global pandemic. In this case, the mediator should gather information from many parties and communities to build and maintain relationships. It would be necessary to ensure that all the key players are prepared to participate at the table.

Conclusion

As disagreements arise, early and effective intervention is crucial to the well-being of individuals, organizations, communities, and society. Therefore, skilled mediators working with individuals to keep problems and disagreements at the lowest level of conflict will promote conversations that lead to early and effective resolution. A mediator, thoughtfully listening and recognizing how individuals explain the dynamics of their disputes, can arrive at a comprehensive diagnosis to help with de-escalation and resolution.

[1] Macfarlane, J., Manwaring, J., Zweibel, E., Daimsis, A., Kleefeld, J., & Pavlović, M. (2016). Dispute resolution: readings and case studies (Fourth edition.). Emond Montgomery Publications.

[2] Menkel-Meadow, C. (2003). Correspondences and contradictions in international and domestic conflict resolution: lessons from general theory and varied contexts. Journal of Dispute Resolution, 2003(2), 319-.

[3] Shonholtz, R. (2003). General Theory on Disputes and Conflicts, A. Journal of Dispute Resolution, 2003(2), 403–.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Burton, J. W. (1996). Conflict resolution: its language and processes. Scarecrow Press.

[6] Felstiner, W. L. ., Abel, R. L., & Sarat, A. (1981). The emergence and transformation of disputes: naming, blaming, claiming. Law & Society Review, 15(3-4), 631–654.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Macfarlane, J., Manwaring, J., Zweibel, E., Daimsis, A., Kleefeld, J., & Pavlović, M. (2016). Dispute resolution: readings and case studies (Fourth edition.). Emond Montgomery Publications.

[9] Felstiner, W. L. ., Abel, R. L., & Sarat, A. (1981). The emergence and transformation of disputes: naming, blaming, claiming. Law & Society Review, 15(3-4), 631–654.

[10] Burton, J. W. (1996). Conflict resolution: its language and processes. Scarecrow Press.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Pinkley, R. L. (1992). The International Journal of Conflict Management, Vol. 3, No. 2, April 1992. pp. 95-113.

[14] https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/campaigns/national-day-truth-reconciliation.html

[15] Singleton, K. (2013). review. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 30(4), 680–685. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033932